The following is the description for The Godfathers, one of the best seminars presented at Tales of the Cocktail this or any year:

A Godfather is defined as a man who is influential or pioneering in a movement or organization. Whilst there are many potential Godfathers and Godmothers in the making now, there are perhaps just four who stand out from the dawn of the Second Golden Age of the Bartender in the USA. Join three of them: Brother Cleve, King Cocktail and The Alchemist as they talk trials and tribulations, sources and inspirations, lessons and learnings from the past and their thoughts for the future. Moderated, curated and wrangled by Angus Winchester.

The Godfathers featured three cocktail legends on the same panel: Brother Cleve, Dale DeGroff, and Paul Harrington. The 90-minute session was led by Angus Winchester, the Vice President of Education and Training at Barmetrix.

In his opening remarks, Winchester said, “I think of them as godfathers to me, all three are hugely significant and important in my career as well.” Winchester noted that these are the American godfathers – were he to expand the scope of the panel to internationals, he would include Dick Bradsell from the UK, Charles Schumann of Munich (“perhaps alongside Dale the only person who actually looks like a godfather”), and the Maestro, Salvatore Calabrese. If he had a bigger panel, Winchester said he would have added Murray Stenson to the American godfathers. “These three guys did it back in the day. They were either sources of inspiration or information, or just great places to get drinks, and really did what a lot of us aspire to do nowadays.”

PAUL HARRINGTON

Winchester told the audience that he started bartending in New York in 1993. During his downtime, he used “this Internet thing” and during his research, “I stumbled across this incredible website called CocktailTime.com. This was really important, because it was the first time I’d actually seen that cocktail recipes weren’t just recipes, they had stories behind them, they had histories. And the drinks [Paul Harrington] was choosing were drinks like the Aviation, the Monkey Gland, the Pegu Club, the Red Snapper. And this was such an incredible source of information for me, to give me something to talk to guests about. Remember, back in those days, people weren’t overly impressed by the wonderful cocktails you made, it was how heavy your pour was and whether you could remember their name, things like that.” Cocktail Time is now archived at The Chanticleer Society.

Harrington’s online persona, “The Alchemist,” was incredibly influential for many other bartenders as well. “This was really a virtual godfather,” said Winchester. “Jacob Briars popped in earlier and he had to come up and shake Paul’s hand, because he said, ‘I’m sitting in New Zealand, I found this website and it really was this link to realizing there were other people around the world who cared about drinks and not just the effect of drinks.’”

Harrington is the author of the seminal 1998 book, Cocktail: The Drinks Bible for the 21st Century, “which is out of print and as far as I’m aware will stay out of print for some time,” said Winchester. After working as an architect at OMS Architecture Interiors and South Henry Studios, Harrington returned to the cocktail world when he opened Clover in Spokane, Washington in May 2012.

BROTHER CLEVE

Brother Cleve is a Boston-based DJ and record producer, and was previously the keyboard player for The Del Fuegos and then Combustible Edison. As the bar manager of the famed B-Side Lounge, Cleve would become the progenitor of the next generation of Boston influencers, which includes Jackson Cannon, John Gertsen and Misty Kalkofen. Winchester said he first met Cleve when he competed in Boston – the only cocktail competition he’s ever entered. He found out they had a common interest in music, what was then known as Space Age Bachelor Pad, Loungecore and the Cocktail Nation. “I didn’t realize how lucky I was, because by meeting Cleve up in Boston I was immediately sort of grandfathered in; I was a legacy now at every single bar I went to.”

DALE DEGROFF

Of course, you can’t have a seminar about American bartending godfathers without King Cocktail, “the Da Vinci of Drinks, the Yoda of Mixology,” Dale DeGroff. His extraordinary influence on the bar world spans three decades, including a stint at the legendary Rainbow Room in the 1980s, where he pioneered a gourmet approach to the resurrection of long lost classic cocktails.

Among his many accomplishments, DeGroff is the James Beard Award-winning author of The Essential Cocktail and The Craft of the Cocktail, and is also a founding partner of Beverage Alcohol Resource (BAR) and founding president of the Museum of the American Cocktail. He recently launched his own brand of Pimento Aromatic Bitters.

After admitting he’s previously described DeGroff as “the bastard child of Tony Bennett and Martin Scorsese,” Winchester said he spent his 26th birthday at the Rainbow Room, and recalled sipping a Sazerac that DeGroff made for him, “as we were sitting at the Rainbow Room, totally alone with that incredible view.” When he interviewed DeGroff for CLASS Magazine, Winchester saw his “wonderful library of books, which again made me realize there were other great books out there that I could buy, beg, borrow and steal.”

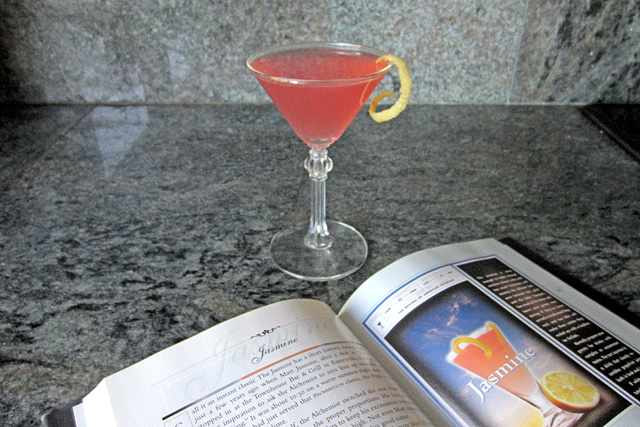

Paul Harrington’s Jasmine

The welcome cocktail was the Jasmine, a modern classic created by Harrington when he was at the Townhouse Bar & Grill in Emeryville, California. (Recipe below.) On a “warm summer night” his friend, Matt Jasmine, stopped by the Townhouse after his shift at Chez Panisse. Jasmine said to Harrington, “Make me something new.” Harrington riffed on the classic Pegu Club, using lemon instead of lime, and subbing Campari for Angostura bitters. His friend took a sip and said, “Congratulations, you’ve just invented grapefruit juice.” [laughter]

EARLY STIRRINGS

The panel began in earnest when Winchester asked the godfathers how they got their start. Harrington said he was two years into college and “sort of going down the wrong path.” He moved back home for a year, and in the summer of 1988 – after turning 21 – worked one bar shift at a nightclub, Charlie’s Bar & Grill in Bellevue, Washington. Only one patron came in that day, and he ordered a Manhattan. “I don’t even know how I knew what a Manhattan was, but I made him a Manhattan.” The guest said it was great, and Harrington thought, “Wow, I guess I must be a bartender.” [laughs]

About two weeks later, Harrington moved back to San Francisco and eventually became bar manager at Houlihan’s on Fisherman’s Wharf. During his tenure, he trained Tom Southwell, who was one of the original bartenders at TGI Fridays. “He’s the one that taught me there’s a respectful way to make drinks. Regardless of how ridiculous the drink was, you follow the recipe for cost reasons, portion reasons, it tastes better when you use the recipe. He taught me to respect the bar and respect making drinks.”

Cleve began his bartender origin story by saying his grandmother gave him a Manhattan when he was eight. (Winchester quickly encouraged Cleve to move on.) Fast forward to the 1970s, when Cleve was a young punk rocker and frequently played at a Boston club called the Rathskeller (aka “the Rat”), where he would always drink Manhattans. In 1985, Cleve joined The Del Fuegos. The band was in Cleveland on the third day of their first U.S. tour, and they went to a place called Shorty’s Diner. The back cover of the menu said, “try a refreshing cocktail,” and it had a hundred drinks on the list. “Wait a minute, there’s only 20 cocktails, right? What the hell are all these other things? What the fuck is a Sidecar?”

Cleve went into a bookstore and bought an old Mr. Boston Official Bartender’s Guide. “I got fascinated by all these old drinks, and I was trying to find a lot of these spirits. What the hell is Creme Yvette, and where do you find these things? A lot of these spirits weren’t available, nobody knew how to make these drinks, but I was fascinated by it.”

Three years later, after the band broke up, one of Cleve’s friends was opening a bar in Boston. “’Want to be a bartender?’ Yeah, OK. Sounds good. The first day at the bar, I looked at the sign. ‘Today’s special: Sidecar.’ My first customer said, ‘What the fuck is a Sidecar?'” [laughter]

DeGroff’s bartender journey began at age 13, when he saw West Side Story in Indianapolis. “I really wanted to be a Jet. I wanted to wear a thin black tie and a purple shirt, and I wanted to live in New York City. That was my dream. I didn’t have any more ambition than to get to New York City one way or the other. Upon arriving in New York, it took about 13 seconds to figure out the only place you wanted to be was in a bar. [It’s] the most interesting place, the most comfortable place, since my apartment was about as big as this table.”

His roommate’s older brother was the “top dog” in an advertising agency, and he got them jobs in the mail room. “What he was, actually, was an Olympic drinker,” said DeGroff. “He had the account, Restaurant Associates, which was the supreme account that every advertising agency in New York wanted. These were the original Mad Men guys. They missed the whole humor on the TV show. These were the funniest men I’ve ever met in my life, they could all be stand up comedians. The best jokes in the world start in advertising agencies and went around the world.”

“They taught me how to order stuff, what to order when and why, very early on. (You could drink at 18 when I arrived in New York, I was 19.)”

DeGroff’s ultimate goal was to become an actor. “I got out to Los Angeles, still harboring the dream to be a movie star. I was working at the beautiful Hotel Bel-Air. God knows how I got this job, I didn’t have a clue. But I realized when I got there that I really had to focus. So I started tasting everything behind the bar, I hadn’t seen any of those products before.”

DeGroff eventually became friends with the hotel’s piano player, Bud Herman, who had played with Benny Goodman. Herman told him, “‘Dale, I know you’re really into this acting thing. But you got a knack for bartending.’ When both my sons were born, I realized that ‘knack’ really better pay off, [because] show business wasn’t. [laughter] “And I went back to New York City. But I’ve had the good fortune of always having a good job. It was just so serendipitous, I walked into incredibly beautiful locations where I learned a lot while I was there. And the second phase of that was to go work for Joe Baum, and that just changed my career.” [applause]

THE AHA MOMENT

The panelists were asked to share their “aha moments,” when suddenly everything seemed to make sense, they could make money and have a career with bartending. Harrington said there were a couple of aha moments. One was being introduced to DeGroff through mutual friends, when Harrington was bartending at the Townhouse Bar & Grill. Harrington had read about DeGroff in trade magazines, and he even made a pilgrimage to the Rainbow Room on Thanksgiving weekend – DeGroff wasn’t there that night. “[Dale] had some college friends that owned a restaurant around the corner from my bar. They would close down their restaurant and come over and have a drink.” One night, one of them told Harrington, “‘My friend from New York would love this bar. He’d love what you do here.’ Who’s your friend? ‘Dale DeGroff.’ Wow, you know Dale DeGroff? We didn’t have Facebook, this was real networking.”

That fall, DeGroff came into the Townhouse and sat at the bar. “I had to go back in the cooler because I was shaking. I think he asked me what I was working on, I didn’t have much to say. I made him a Martini.” DeGroff and his friends went drinking in San Francisco. Later that night, as Harrington was closing down, DeGroff came back to the Townhouse and told Harrington, “‘You know, that Martini was the best drink I had tonight.’ I took that to heart.” (DeGroff added with a smile, “Just for the San Francisco bartenders, this was 1992, guys.”)

Another aha moment for Harrington was meeting Charles Schumann in Munich. “So there were a couple of events like that in my life, where bartending was not a career then, but it sat well with me, it’s like, ‘I’m supposed to be doing this.’ I’m in this network of people. There’s a bigger reason.”

DeGroff said, “I got a waiting job at Charley O’s, which was a Joe Baum invention, one of his most successful bars. It was in Rockefeller Center, it was just a lively, raucous New York bar and grill – classy and divey at the same time, it was just such a great place. You never knew who was going to walk in – they used to have the St. Patrick’s Day breakfast there, with the mayor, the bishop and everybody.”

In 1975, Charley O’s was sold to Peter Aschkenasy. Charley O’s had the contract to do all the parties at the mayoral residence, Gracie Mansion. The two bartenders that taught DeGroff had no interest in this, what with all that loading and unloading. “The money they made behind the bar was so good, and they were union and didn’t have to take this job.” DeGroff jumped at the chance. “So off I went as a waiter. Rupert Murdoch was being given the keys to the city. I tended bar, and I felt better and better as the evening went on. This stuff is easy! I felt really good back there, this is what I want to do. And I go back, and I ended up getting the service bar job.”

“Flash forward many years, and I’m in SoHo, in a duplex apartment owned by Rupert Murdoch,” DeGroff continued. “Working his birthday party. He walked up and said, ‘You’re the hot shit cocktail guy.’ [laughter] And I said, ‘Actually Mr. Murdoch, our fortunes rose together in this city.’ So my aha moment was that day at Gracie Mansion.”

Cleve said, “I’ve always liked bars and I’ve always liked bartenders. They made sense to me. They were great guys to hang out with, they could talk about anything, they knew a lot. So in 1988 when I got behind the bar myself for the first time – I’d been in ‘show business’ for 10 years or so at that point – I realized it was the exact same thing. You’re on stage. I realized that what I had admired in these people that had done this before me, that I unconsciously learned a lot from them. So what was the difference between doing this and playing rock and roll? I didn’t have four other guys.”

BARTENDING AS A CAREER

Winchester asked the godfathers, how did they feel about people who want to grow up and be bartenders? “It’s a legitimate industry now,” said Harrington. “When I bartended, for whatever reason I decided, ‘I’m going to do this until I’m 30.’ I worked my way through school, it was a great social life, it was like being a rock star. Now it’s a legitimate business, there’s more money and opportunities. It’s a legitimate career choice, for good or for bad.” He added, “I live in a small rural community, we spend a lot of time on country roads, and you come across a bar and you find someone there… they don’t have any of these ingredients. You’re lucky if they have cold beer. But there’s still some great bartenders out there.”

DeGroff concurred, “It is in fact a very good place to go. And you can go in a lot of different directions. There’s mid-six figures to be made if you handle your cards right. There are a lot of corporations out there right now that need beverage professionals at the highest level, and those are guys who know more than I do. They know everything about wine, beer, sake, cocktails, and service. They know it. They’re sitting in this room… some of them are eminently employable by these very large, mid- to luxury-level chain restaurant groups, or luxury hotel groups. If that’s what you want to do, if you want to make big money, you can actually do it as a bartender. You couldn’t make that kind of money as a bartender before.”

“If you want to go the more ‘spiritual’ route as it were, there’s people like Sean Kenyon. He has a couple of bars, he loves the people he works with, he nourishes them, he trains them, he’s an incredible employer. He’s happy doing what he’s doing, he’s probably never gonna make mid-six figures… or maybe he is now,” DeGroff laughed. “Of course, the primary thing you have to ask yourself when you step into this role is, ‘Do I like people?'” Winchester added, “Everyone says, no one cares how much you know until they know how much you care.”

“OLD” IS THE NEW “NEW”

All three panelists are known for resurrecting old cocktails or championing classics, rather than crazy signatures and modern drinks. What made them so interested in these older cocktails? “There were so many of them that I had no idea [about],” said Cleve. “Like I said, I drank Manhattans, Old Fashioneds, Rob Roys, Martinis, etc. In Boston, there was a group that started having cocktail parties in the 80s. It was a very punk rock thing. “My friend The Millionaire – who’s the leader of the band, Combustible Edison – said that ‘Getting into cocktails was the most punk rock thing I could ever do, because nobody did it.’ Nobody drank them. It was like going to a bowling alley or a drive-in movie theater. All those things were dying out at that time, in the 80s. There were these people that would have these cocktail parties, and dress up – kind of like I am today – and listen to easy listening records, Tiki music and Martin Denny records, and [we’d] pretend we were sophisticated even though we were a bunch of goddamn punk rockers.”

DeGroff said, “My route into classic cocktails of course was Joe Baum, who said, ‘I want a 19th century bar at the Rainbow Room.’ That was all I needed to hear. I wanted the gig real bad, so I went to work at it. Obviously that, mixed with going back to the original recipes, and the fresh juices and all that, it made a nice little package. I didn’t even think about signature cocktails for a while. I was having a helluva time figuring out how to do the classic ones.”

“I got my first menu out at the Rainbow Room, and it was a disaster. I had 26 of the hardest drinks to make, ever. And these guys had never made them before, and all of a sudden they were nine deep at the bar. There was no ‘soft opening.’ We opened the doors and there were thousands of people. So I took the first menu out after six months, which really pissed Joe off because it cost a fortune – laser graphics, glossy everything. And I’m ripping it out of service and Joe was like, ‘Jesus Christ, Dale! We put a lot of money in this thing.’ I said, ‘It’s not working.’ Joe hung in with me, it took us a year to make it work, but eventually it worked.”

It was Baum who told DeGroff to go find Jerry Thomas’ How to Mix Drinks: Or, The Bon Vivant’s Companion. “I went to bookstore after bookstore. The S.O.B. never told me it was written in 1862!” [laughter]

For Harrington, part of the intrigue of classic cocktails came from his aha moment, when DeGroff asked him what he was working on. Harrington realized he was focused on service and technique, and not necessarily recipes. After that night, he began photocopying and reading old cocktail books from the UC Berkeley library. “When I started bartending, you made Negronis for your bartender friends if you wanted to play a joke on them, and you muddled a Kamikaze if you really respected them and wanted to make something fresh. So that instinct was there to use fresh juices and take care in making cocktails.”

“The first drink I remember coming across in an old Trader Vic’s guide was the Pegu [Club]. I looked at it and said, ‘Well, that’s just a Kamikaze with the vodka switched out for gin, and add some bitters.’ The next day, I went into the bar and made it. ‘Wow, that’s good.’ That was inspiring. That was my original search, looking for drinks that you could promote to people, that they would be familiar with. Personally, I enjoy spending time with people who drink spirits more than people who drink beer and wine. So I was trying to build that clientele.”

“I never worked off a menu, this was something I would offer to people if I thought they’d be up for it.” DeGroff noted, “Nobody had menus, it wasn’t just Paul. In that era, you went to bars, there were no cocktail menus anywhere.”

Harrington continued, “I bought a Charles Schumann book, Memories of a Cuban Kitchen, that had a bunch of Cuban cocktails in the back of it – the Hemingway Daiquiri and the Mojito. They were just fun to make. In architecture school, they teach you that you can do anything with design, but you have to have a reason for doing it. To bartend, I have to have a reason for making these drinks. The classics was an easy… all the ingredients weren’t there. Some drinks you couldn’t make, you couldn’t get the product. But you’d run across the product at times. So that was it, I found that rewarding.”

Dale DeGroff’s Accidental Sour

The next cocktail was DeGroff’s Accidental Sour, made with Tanqueray No. TEN, Pineau des Cherantes, apricot liqueur and lemon juice. The name was inspired by the story behind the pineau, a “wonderful bit of lore” as DeGroff calls it in his recipe for the Rainbow Sour, from The Craft of the Cocktail. According to the story, a cognac maker accidentally dumped freshly squeezed grape juice into a barrel that was half-filled with cognac, not knowing what was inside. He was so angry that he set it aside, thinking the cognac was ruined. A couple of years later, “he tasted it and thought, this is pretty darn good. I’ve never met that guy, and David Wondrich hasn’t corroborated this yet, so it’s still lore.”

SIGNATURE DRINKS & MODERN CLASSICS

When asked about his thoughts on signature drinks, Cleve answered, “I think it’s intriguing, because we did go through that period where we were going through all these books and finding these drinks that hadn’t been made in ages. Maybe they never even really made them – how many Last Words were made in the 1920s, who knows?” Today, when someone goes to a craft cocktail bar, it’s likely they’re going to that specific bar to get those specific drinks. Cleve continued, “You’re not necessarily going to get them anywhere else. So that’s what the appeal is of a certain bar or a group of bartenders, individually and collectively. I find it fascinating, actually. If I want to have a Last Word, I can order it. I certainly hope every bartender knows how to make that, or a Manhattan or a Martini or whatever. The idea that you can have something completely original is good.”

Winchester posed the question, why so few modern classics? DeGroff quickly answered, “How can we tell yet? For a car, it’s 25 years to become a classic.” Winchester replied, “There are certain [modern] classics – the Bramble, the Penicillin.”

“I think Paul Clarke pulled it together pretty well in his Imbibe article,” said DeGroff to enthusiastic applause. “He mentioned several that we all love to drink and love to make, and he hit a lot of them right on the head.” DeGroff added that there were other cocktails from Europe, citing the Vodka Espresso as a popular example. “Names. Names are so damn important, that could be the classic right there if you get the right name.”

THE ALCHEMIST

Winchester asked Harrington, “With HotWired, you were the virtual godfather. How did that come about?” Harrington said he left the Townhouse to help open Enrico’s in SF. One night, two writers stopped by to write an “ironic article” about great summertime drinks to have in San Francisco – ironic, given the city’s notoriously cold summers. Harrington talked about the Mojito and the Hemingway Daiquiri. “Back then, writers were writers and bartenders were bartenders, there wasn’t the crossover we have today. So they loved it, and wrote an article about it.” One of the writers, Gary Wolf, became the editor of HotWired, the first commercial web magazine and sister publication of Wired magazine. Laura Moorhead and Graham Clarke – both fans of Combustible Edison, natch – approached Wolf with the idea of doing a cocktail website. Wolf referred them to Harrington, who was transitioning into architecture, but welcomed the income that a weekly column would bring. “It was great, because it was a chance for me to write down my thoughts about the industry and the cocktails that I’d been making.”

Once a week, Harrington would go to the Wired offices and make half a dozen drinks. There were initially 12 writers, and Harrington would tell them what he knew about a drink to get them started on research. The writing was a collaborative effort – it took about six months to get enough content to launch the site.

During this time, Moorhead – who later co-authored Cocktail with Harrington – helped him create “The Alchemist” persona. “[Laura] helped me craft words, she knew what I was saying and she knew what the aesthetic was, what I was trying to do with classic cocktails. It was a lot of fun.”

Cleve mentioned that a lot of his clientele in Boston were from the tech world. “There were no smartphones back then, so they would print the pages from HotWired with Paul’s drinks and come in and say, ‘Can you make me this?’ Then they brought the book in after that came out.”

NEXT: The University of Bartending, Secrets to Success, the Cocktail Nation, “Show Me the Money!” and more in The Godfathers Part Two.

The Jasmine, from “Cocktail: The Drinks Bible for the 21st Century”

Jasmine

Created by Paul Harrington

Ingredients:

- 1.5 oz gin

- 0.25 oz Cointreau

- 0.25 oz Campari

- 0.75 oz lemon juice

Preparation:

- Shake with ice and strain into a cocktail glass.

- Garnish with a lemon twist.

[…] “The Godfathers” at Tales of the Cocktail: Part One […]

[…] of the Godfathers of modern cocktail culture, Brother Cleve is the living embodiment of “Booze and […]